Introduction

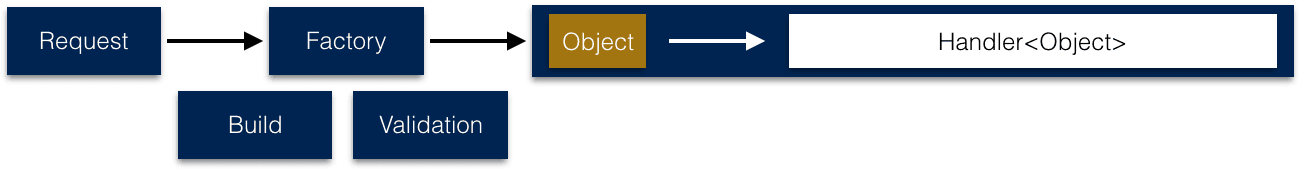

These are notes taken from the process that we use in my team to deliver new features. In the project where I spend most of my time, we combine the maintenance of an important amount of legacy code that we try to improve with the design of new features. Quite frequently, we face scenarios like the one depicted in the image:

Quite common for a big distributed application and over an also frequent protocol, as HTTP.

Maintainability 101

These ideas aren't new. Separation of concerns, levels of abstraction and loose coupling. When applied consistently they should lead to something similar to Cockburn's "ports and adapters" architecture.

The gist of it: You want to have your business domain completely isolated from its dependencies, as a database or the user interface. That isolation is accomplished with ports (the interface that establishes the contract for external communication) and the adapters (converts the external message into something that can be used into the application).

You can read also Mark Seemann's approach to the topic, where he affirms that this is not so different to a layered architecture correctly following the Dependency Inversion Principle.

Isolating the feature

The initial step is completely isolating the input/s to be used to fulfill the operation. Typically, that means making sure that we treat the request object that we receive as a DTO, with data and no behavior and also that we transform it into something different before it goes into the logic. At the boundaries is ok if we do not have proper objects. Same principle can be applied if we need to communicate with other systems and the data is going to flow out of the feature.

If we suffer any change at the inputs the only maintenance point will be the logic that performs the transformation from DTO to meaningful object in the context our feature. There are several strategies to perform that transformation.

Depending on the complexity of the mapping, solutions as AutoMapper, Dozer, etc. can work pretty well. If the actual logic that builds the object is not straightforward, creating a factory can be a better way of expressing the transformation. The factory can orchestrate the validation and actual creation of the new object. The result is a different object derived from the input and extended with more information and behavior. The feature only accepts that resulting object.

Commands and command handlers

We express a lot of our features with commands a command handlers, but don't assume any fancy architecture behind! Most of our operations run synchronously. Commands and command handlers allow us to separate what we are going to do from how we will do it.

That being said, we don't know if in the future some of this operations will go through a bus running asynchronously. This could be an arduous matter but we can design our code to exhibit a few design traits that will make the transition easier. Only a few thoughts:

-

Commands by definition should be immutable, we cannot change their internal state once created (they do not need to change during their lifetime). That will allow us to treat them as value types whose identity is derived from the value of their properties.

-

The handler will need to have another important property, the operation must be idempotent, meaning that you can apply it several times but the outcome should not change after the initial application. That is required because sometimes we cannot guarantee that the command will be executed only once over the domain (failure conditions on your code or the network). There are several approaches to this problem.

-

Ensure that the command will be serializable. If at some point in the future we need to transfer that command to an external system (such as the bus that we mentioned) the data will be translated into something else. Do not put anything inside that you cannot serialize.

Exceptions

I would include as 'maintenance' the ability to have some metrics about performance and errors after the feature has been deployed, so logging the exceptions is something that we do.

If you are not going to do anything specific with the exception, it only makes sense catch it at the boundaries of the process/feature and control what data structure you will use to communicate them. It is important to remember that logging is a cross-cutting concern, you shouldn't be seeing much code about that in your business logic. Accordingly, it makes sense to have a single piece of logic that handles the conversion from the exception to the data structure that will leave your process. If you are working with HTTP as we do, make sure meaningful status codes are provided. A few examples:

- 400 if the exception was caused by bad inputs (include the input!).

- 403 for authentication issues.

- 503 if you find a downstream dependency broken.

If you are going to re-throw a new exception after catching one (because you want surface a different one) make sure that you find some mechanism to respect the context. For instance, in .NET you will find the InnerException property, and Throwable.getCause() for Java.

Unless you have a good reason, it should only be one place for logging. It is easy to find codebases where writing the exception to the log happens in several places leading to duplications. It really makes harder to read the logs.

Code Reviews

Keep the code review thorough. Sometimes achieving "loose coupling" requires a high level of attention to detail that can be tricky when you are close to your deadline. Good, honest and sincere feedback from your peers is a rare gift. Use it.

I know that 'code coverage' is controversial metric, more meaningful to find untested parts of the codebase than as a numeric expression of how good your tests are. Anyhow, we analyze the coverage for the namespace of the feature and we include it in the review description.